Whispers in the Dark – Part Four

No day is dark forever, no pain too much to bear, no sadness without joy.

﷽

Trigger warning: This part of my story contains references to medical trauma and sexual assault and murder. Please read only when you feel emotionally ready, and pause whenever you need to. If it feels heavy, step away. Take a breath. Remember: Allah is Al-Latif — the Most Gentle —and He never burdens a soul beyond what it can bear.

Though written in a storytelling style, this is not fiction. Every word is drawn from real events, a real illness, and a very real battle for my soul. I chose to frame it in narrative form so you could step into the experience — the darkness, the whispers, and the mercy that carried me through.

Important: If you are reading this via email you will need to click here for the full newsletter as the post is too long for email.

Hospital West – Awakening

I was safe.

My body released a trembling sigh, the kind that escapes when survival finally feels real. As the nurses wheeled me into the new hospital room, I drew the curtains around my bed with deliberate hands. A small act of control after days that had stolen every ounce of it. Behind the curtain, I let the silence wrap itself around me.

I closed my eyes and tried to remember what day it was. My mind, thick with fog, spun around the same question as if solving it might restore a sense of control. I had just escaped an attempted sexual assault—perhaps worse; I will never know what Mr. van de Laar truly intended—and yet, instead of processing the terror, I fixated on time. How long had I been hospitalized?

I reached for my phone. The screen glowed like a fragment of another world. Two and a half weeks. My chest tightened. Two and a half weeks?!?!

I tried to retrace the days, but they dissolved into one another—nurses, morphine, lights that never dimmed. The realization hit like cold metal against skin: I had been lost in a loop of pain for more than fourteen days, breathing but not present.

The weight of what had happened settled over me. My muscles stiffened; fear made me small again. I froze—as I always do when terror visits. But this time, I refused to remain its prisoner.

I forced myself to stay with it—to sit inside the fear rather than flee from it. I replayed everything, moment by moment, from the first pulse of pain to the instant I arrived here. I reached for my notebook, the one I had begun only days after surgery, where I scribbled fragments of each day before they disappeared into the blur. Turning those pages felt like excavating another life.

The memories came in waves—days strapped to machines, the endless sound of wheels rolling me from one specialist to another, the metallic taste of contrast dye and antiseptic air. I had survived, yet survival came with questions I couldn’t ignore.

The whispers—I needed to know if they were real. The voice in the dark that had taunted me when I was weakest—was it my mind, or the Shaytan himself? The analyst in me demanded evidence; the believer in me already knew the answer.

After a lifetime of being told what to think, how to feel, how to exist, I refused to let anyone define my truth—not this time. So I did what I always do: I researched. Pain became my teacher; the hospital bed my desk. I had time—endless, aching time—and I decided to use it. Despite the continuous pain, I began re-studying seven modules from an online course I’d taken in 2021, Deception: A Study of Shaytan, with Sheikh Saad Tasleem. I remembered him explaining how to discern between your voice and the Shaytan. This time, I didn’t just want to understand; I wanted to reclaim authority over my own mind.

By the final module, the Sheikh confirmed what my heart had already knew: those dark whispers in the night were not mine. They were the whispers of Shaytan—inviting me to eternal damnation. I had faced my enemy, and Allah saved me. But one day the Shaytan will whisper to me one last time, and to be ready for that day would require me to hold onto the rope of Allah, knowing my very soul is depending on the mercy of Allah.

In that stillness, reflection deepened. The more I breathed, the more I saw the shape of my life—and the truths I’d been denying for years.

Only a handful of people know the true extend of what I’ve endured over the last several years. And only Allah knows the full story. Yet on that day in December when the pain began, I felt strangely light, as if something had been lifted. The tahajjud that morning felt like a gift wrapped in Allah’s mercy. Just before the agony struck, I had said aloud, “2025 is going to be an awesome year, inshaaAllah.” It hadn’t felt like wishful thinking; it felt like a promise from Allah (Allah knows best). My mind wandered back to another time I felt Allah’s mercy.

Back to the day my beloved grandmother passed away, 8 June 2023—the same day smoke from the Canadian wildfires draped New York City in a blanket of smoke. Even hospitals were filled with it. The sky turned the color of grief. It was as if Allah had mirrored my sorrow in the heavens. That eerie stillness felt like a sign—an intimate acknowledgment from the Lord who sees every tear.

Loss has long since shadowed me: no longer a wife (walking away from him difficult but necessary), no longer a granddaughter, or a daughter, a mother only in longing, and now my health too slipping through my hands. I was adrift. Yet beneath that drift was conviction: that even in the wreckage, Allah’s plan held beauty I could not yet see. Perhaps 2025, the year that felt like an ending, would reveal itself as the beginning of something extraordinary. Hope itself became worship. Trust became my anchor.

Allah says in the Qur’an:

> لَآ إِكْرَاهَ فِى ٱلدِّينِ ۖ قَد تَّبَيَّنَ ٱلرُّشْدُ مِنَ ٱلْغَىِّ ۚ فَمَن يَكْفُرْ بِٱلطَّـٰغُوتِ وَيُؤْمِنۢ بِٱللَّهِ فَقَدِ ٱسْتَمْسَكَ بِٱلْعُرْوَةِ ٱلْوُثْقَىٰ لَا ٱنفِصَامَ لَهَا ۗ وَٱللَّهُ سَمِيعٌ عَلِيمٌ ٢٥٦

Let there be no compulsion in religion, for the truth stands out clearly from falsehood. So whoever renounces false gods and believes in Allah has certainly grasped the firmest, unfailing handhold. And Allah is AllHearing, AllKnowing.

That ayah had captured me the first time I encountered the Qur’an. I had been searching since girlhood for something unbreakable to hold onto. Raised in a home where church and Bible study were obligatory, I felt the hunger for truth long before I had a name for it. Islam gave me the rope I had been reaching for all along.

Allah Subhanahu wa ta’ala didn’t hand me answers all at once; He unveiled them slowly, like dawn creeping across a dark horizon. Even here—in this sterile room, stitches still raw, mind teetering on the edge of exhaustion—He steadied me through His words.

Allah had withheld many things I once prayed for: six children, a marriage in the dunya and Jannah, and the chance to serve my parents in their old age. They died young; I never got to fulfill my childhood promise to care for them. I wasn’t by my grandmother’s side when she returned to Him. My siblings—five left out of six—stood at varying distances; only one stayed near during my illness.

Yet for every loss, He gave a blessing wrapped inside it. That paradox sustained me well. Hospitalization forced what I had been too restless to do: slow down. No meetings, no classes, only the hum of machines and the rhythm of my own breath. In that forced stillness, I finally met myself again.

I saw the little girl I used to be—the one who scanned winter soil for the first snowdrop on her walk to school, whispering “Will it be white this year or purple?”

The one who ran to the gate at sunset just to watch the sky turn orange, ochre, kissed by hues of purple. She wondered, “Who paints it this way every evening, and why?”

She had always sensed Him. She simply hadn’t known His name yet.

As an adult, I’d traded sunsets for deadlines, awareness for distraction. I chased the dunya and called it duty. The Qur’an calls that heedlessness (ghaflah), and I was drenched in it.

Now, confined to four white walls, I longed for a glimpse of sky. The corridors held no windows; I peered from the thresholds of other patients’ rooms, hungry for a sliver of orange light, but my corner room never caught the sun. The absence stung. It felt like a quiet admonition from my Lord—a reminder of all the invitations to pause that I had ignored.

Ya Rabb, forgive me.

So I made a vow: when I left this place, I would slow down—not just my pace, but my soul. The real struggle, I realized, would begin not here in convalescence but when the world resumed its rush.

I remembered the hadith:

“Composure (calmness) is from Allah, and rushing is from Satan.”

The Most Painful Truth

I come from a large family—six of us siblings remaining.

The details of our private wounds belong only to us, but the lessons they birthed belong to everyone who has ever loved too much. I learned that I had carried guilt for things I never did. I allowed disrespect from my siblings because I mistook tolerance for patience. That in craving their love, I abandoned my own boundaries. When the anger finally quieted, I faced the rawness beneath it: grief, which led to finally being able to accept and embrace the painful truth.

Allah had not given me the rizq of my siblings’ love and support, and there is goodness in it.

I remembered the story of Yusuf (as) and his brothers, and my heart became contented.

It’s a simple truth—bare and merciful. By accepting my qadr (Divine Decree), I stepped into a different kind of power: the quiet strength that grows from taqwa.

Alhamdulillah.

I began the slow reclamation of myself, beginning with my self-respect and my right to joy. I have always been a joyful person; I see blessings where others see nothing but problems. Some people can’t stand light when they’ve grown used to shadow. But I love life, I never stay down or sad for long, and I am grateful Allah Subhanahu wa ta’ala made me this way.

Regarding my siblings, I will answer their calls for help, yes—but I will no longer bend until I break. I will not chase love that must be begged for. I no longer tolerate any disrespect. Instead, I chase the One, the Source of Love and Respect, Whose love never runs out. The rope of Allah has truly become my lifeline.

Their rejection, I finally understood, was a source of protection. Had they embraced me, I might never have learned to anchor my heart in Allah alone.

Weeks 3 - Tawaf Hospital West

The medical mystery followed me like a shadow, yet the air in Hospital West felt lighter—almost merciful. My new surgical intern, Dr. Jong, appeared one morning . He looked like a Greek statue—blond hair, eyes the color of the ocean—yet there was no vanity in him, only gentleness. He never stood towering above my bed; he would pull a chair, lean forward, and meet my eyes as if to say, I see you, not just your case.

By the end of week three, Dr. da Castro, my surgeon, came to meet with the surgical interns. I didn’t see him that day—only felt the ripple of his presence through the way everyone straightened. Afterward, Dr. Jong returned for an extra visit, his hands clasped, his gaze fixed somewhere near the floor. His voice trembled slightly as he told me more about my surgery than anyone had before: that my organ had torn in five places, that it was complicated beyond what the initial reports described. Even then, I sensed he was shielding me from the worst details.

“I know walking is painful,” he said finally, regaining his usual composure. “But it’s vital for your recovery that you walk daily.”

Those words became a mission. Purpose has always been my oxygen. Without it, I drift. So I walked.

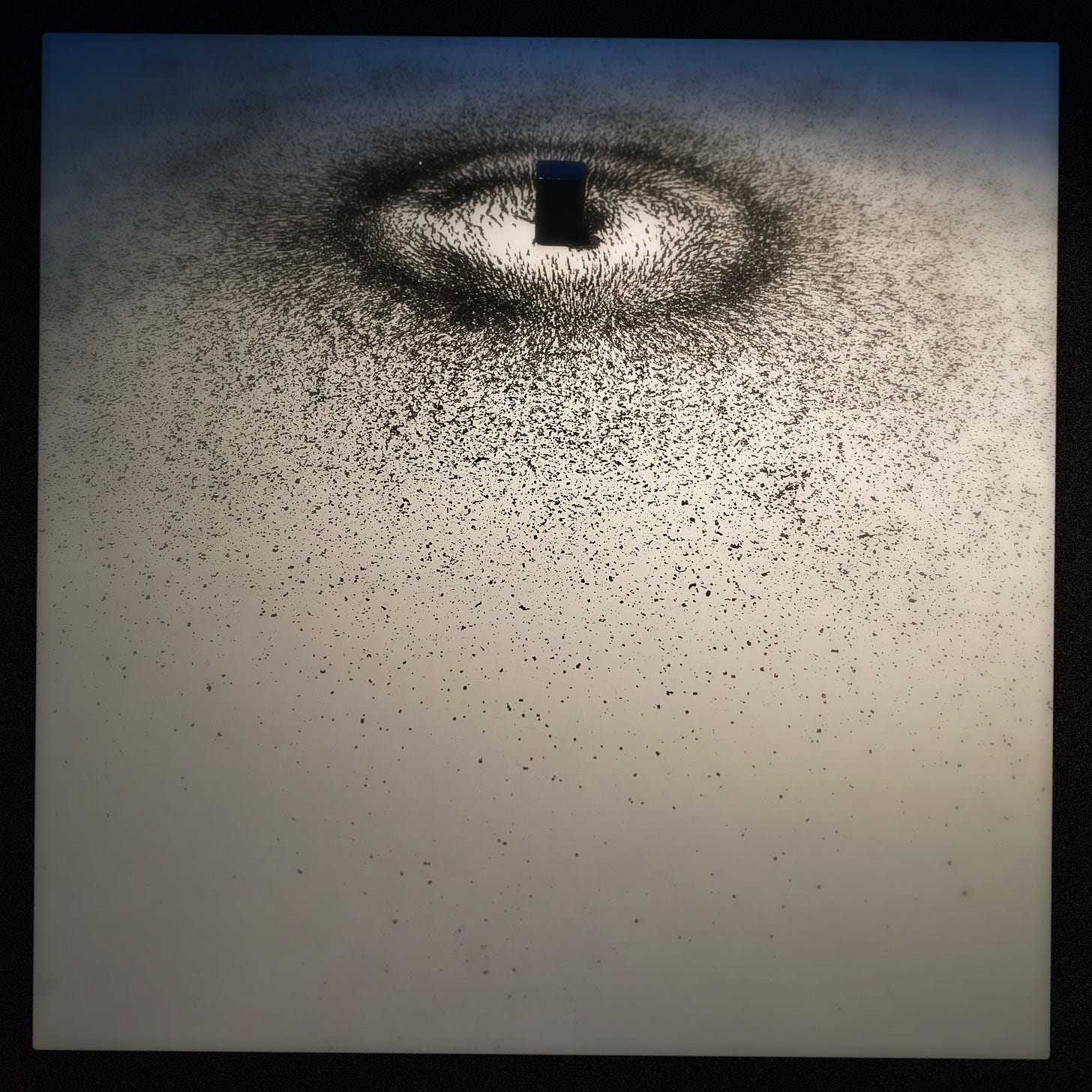

At first, my steps were timid, measured—one hundred meters per day of trembling resolve. The hallway looped like the tawaf around the Kaʿbah, and in that resemblance I found meaning. Though confined to a hospital, my heart was still circling His House. Each step became dhikr; each round, a supplication: Ya Allah, heal me so I may one day visit Your House.

Soon I was walking kilometers, the IV pump trailing beside me like a stubborn companion. When its battery died, I sat in the lounge to recharge it, keeping my tongue wet with dhikr. The nurses began to expect me somewhere in the hallway; even the doctors learned my rhythm, searching for me in the corridors instead of my bed.

By the end of week 3, though, the scans told a truth my body already knew: I was not improving. Liters of bile continued to drain. Without change, I couldn’t be discharged; it was too dangerous. CT scan after CT scan revealed no shift.

Still, I held onto the hadith: For Allah does not create any disease but He also creates with it the cure, except for old age.

The researcher in me awakened. If there were a cure, I would search for it.

The pain had not erased my curiosity—it sharpened it. I pored over medical journals on my phone, following one study to another until, by the will of Allah, I found a treatment used in Japan: Kampō (herbal) medicine. Common spices, familiar and harmless. I showed Dr. Jong the research. He couldn’t prescribe it, but after consulting, he said gently, “It’s safe to try.”

I asked my younger brother to bring the ingredients, measuring spoons, and I made dua istikhara. And then I walked some more—walking and making dhikr, walking and reciting Qur’an, walking and whispering duaʾs between breaths—until I could no longer tell where movement ended and remembrance began.

The corridor became my Mecca.

Week 4 – Hospital West

At the start of week four, the spices arrived. I calculated the dosage of the Kampō medicine formulation and drank the mixture, three times a day for the next six months.

By morning, the bile had reduced. Two days later, it stopped completely. SubhanAllah (Allah is free from imperfection).

I was still intubated, the tube scratching my throat like sandpaper. One night, while showering, a violent sneezing fit seized me. On the last achoo, the entire tube slid out and fell against the tiles. As it hit the floor, I burst into tears. The nurse came running.

“We can wait a bit before calling the doctor,” she said softly.

The thought of being intubated a sixth time broke something inside me. Tears poured until exhaustion took over. Hours later, by Allah’s mercy, the nurse advised that re-intubation was unnecessary.

I whispered Alhamdulillah through raw sobs. I knew in my bones that Allah had saved me once again. The tube’s pressure had been harming more than my windpipe; its removal felt like deliverance.

By the end of week four, I was permitted to drink water. The sweetness of that first sip defies language. It was not mere water—it was life touching my tongue. When they added green tea and then coffee, I felt blessed beyond words. The kitchen staff learned exactly how I liked it—coffee with milk, just right—and they smiled each morning as they brought it to my tray. They frowned, though, at the line that still forbade food. Their eyes carried the empathy words couldn’t.

The surgical ward soon was overflowing with daily visitors—but not for me. A Turkish mother, not much older than sixty, was dying. Her children surrounded her bed daily; grandchildren hovered like anxious stars. Their grief clung to the hallway air. Each time I passed her room on my tawaf, I whispered dua for her soul and for theirs.

She had the six children I once dreamed of. And yet, she was leaving them. The contrast pierced me: how life unfolds in ways only Allah comprehends.

A few doors down was another mother—also Muslim—but her room remained silent. No visitors. I wondered about her story, about mine, about what truly matters before we return to Him. How do I want to live the rest of my life? How do I want to meet Allah?

My grandmother’s voice echoed in memory. During her last Ramadan, we had listened together to Yaqeen Institute’s Jannah series. By then, cancer had anchored itself deep within her, and she knew her time was near.

“Dee,” she’d said softly, “it comforts me. I know what I have to look forward to, God willing.”

At the end of each episode she would close her eyes as the last ayat of Surah al-Fajr were recited—and her face would shine with peace.

My grandmother was the woman who taught me to love Allah. She taught me to trust Him, to speak to Him as One who always listens. Because of her, I sought Him. And in April 2020, at the age of 85, Allah honored me with guiding her to say the Shahada (the Declaration of Faith). Nearly every day after that, I would call her and teach her Islam and how to recite the Qur’an. She learned quickly!

Ya Rabbi, thank You for those moments. Grant her Jannah al-Firdaws, ameen.

Now, in this hospital room, I was alone. Yet solitude no longer felt empty. It became a sanctuary where I could finally be closer to Allah than I had ever been in my life.

On Jumuʿah of week four, I returned from the musallah on the second floor to find the hallway unusually still yet packed with people whose faces were solemn. The Turkish mother had passed away just after Fajr.

Her coffin, wrapped in green cloth, rested in the corridor. More than a hundred mourners lined the walls—family, neighbors, friends watching and making dua as she was carried out. I stepped aside, hands clasped, tears blurring the scene. I didn’t know her life, but I knew her ending was surrounded by love.

Ya Allah, grant her Jannah, ameen.

As the procession disappeared, I thought of the Angel of Death, and that it had been in these same halls, entered this same air. One day, he would come for me, too.

We are all travelers between two calls to prayer—the adhan at birth and the janazah at death. Watching her coffin pass reminded me that this dunya is a brief corridor between those sounds. It is only Allah’s mercy that will deliver us safely to the other side.

The thought left a permanent imprint on my heart.

Day 40 - Hospital West and The Sprout

Almost six weeks after the first pangs of pain ripped through my body, the doctors agreed to discharge me. Not because I was healed, but because there was nothing more they could do. The PICC line stayed in place; my body still couldn’t sustain itself through food alone. But the bile had stopped, and my organ was functioning enough to survive.

As dawn brushed the sky, I sat in the lounge area waiting for my discharge papers. The night nurse smiled as she handed them over. I opened the Qur’an app on my phone and began to recite Surah ar-Rahman. From the very first ayah the tears came flooding. By the final verse, I was sobbing uncontrollably. The mercy of Allah felt so close it hurt.

All the way home, I wept.

When I entered my apartment after six weeks away, sunlight spilled through the bay windows like liquid gold. And there, by the window, the sprout I had left behind had grown into a small, sturdy plant.

I broke down again.

Narrated Abu Huraira:

Allah’s Messenger (ﷺ) said, “The example of a believer is that of a fresh green plant the leaves of which move in whatever direction the wind forces them to move and when the wind becomes still, it stand straight. Such is the similitude of the believer: He is disturbed by calamities (but is like the fresh plant he regains his normal state soon). And the example of a disbeliever is that of a pine tree (which remains) hard and straight till Allah cuts it down when He will.” (See Hadith No. 546 and 547, Vol. 7).

I saw myself in that plant—bent, weathered, yet still holding onto my relationship with Allah and determined to be a better believer. The winds had howled, but they hadn’t broken me. In that moment, I understood: every storm had been a form of mercy, every tear an irrigation of the soul.

A Ramadan of Healing

A few days after returning home, I found myself back at the hospital—this time not as a patient in crisis, but as a woman seeking answers. It was my first meeting with Dr. da Castro since the surgery.

As Dr. da Castro began to tell me the full story of my surgery, I turned to my younger brother in disbelief.

“I had your organs in my hands,” Dr. da Castro said.

“The instruments didn’t work. That’s why I had to cut you open and use my hands. The complication is caused by scar tissue. We need to wait until the end of March. Scar tissue formation goes through stages. We won’t know until the next CT scan if you need another surgery.”

“Nooooooooo,” I said. My reaction made Dr. da Castro’s eyes widen.

I regretted that Alhamdulillah hadn’t been my first reaction, and started to train myself to make sure that would be my default, no matter what the news on the 27th of March would be. I thought to myself, “Isn’t that during the last ten nights of Ramadan?”

The next visit to Dr. da Castro for the results of the CT scan did end up corresponding with the 27th day of Ramadan.

The months at home following my discharge unfolded in quiet rhythm—nurses in the morning and afternoon, exhaustion, slow experiments with food, my best friend’s tender hands cutting off all of my hair because it had died. Each strand that fell felt like an old life shedding itself. My skin flaked, my body shrank, but my soul swelled with gratitude: I am alive.

When Ramadan arrived, it wrapped me in the kind of peace that only comes after surviving. I joined Deen and Chai, a sisterhood of women bound by the Book of Allah. Together we recited, reflected, and cried. I had been sharing monthly Sisterhood Saturday reflections, the last Saturday of every month, before my illness; now I returned to them, fragile but willing. The last two weeks of Ramadan I did most of the daily tadabbur reflections, each one a thread of light weaving me back into life. It is only by Allah’s will and grace that I was able to have the strength to share those reflections and lessons I drew from His Book. Alhamduliah.

On the twenty-seventh of Ramadan, the CT scan results confirmed what faith had already told my heart. The scar tissue had stabilised; my body was ready to eat again. No further surgery would be needed. The PICC line would finally be removed.

Allahu Akbar. Mercy upon mercy upon mercy.

Formal Complaint

Months later, the August sun warmed my skin as I sat outside a coffee spot my younger brother and I had discovered—a new writing space that smelled faintly of roasted beans and possibility. He said it reminded him of being in an old Amsterdam living room, and it felt like that to me, too.

Amsterdam shimmered that day. The canals sparkled as if the city itself was exhaling with me. After months of convalescence, I was rediscovering myself in the familiar streets: new friendships, revived dreams, and a clarity about how I wanted to spend the rest of my life. I went from drifting to slowly finding a new purpose.

But one unfinished chapter pressed against my heart: the doctors who had misdiagnosed me. I needed to face them; closure required confrontation.

I sat on the bench, my flat white next to me, and I wrote out a formal complaint. Within days, Dr. de Bruin—the first doctor who had misdiagnosed me—requested a meeting at my home. He arrived with his supervisor, nerves visible in the way he adjusted his sleeves.

“Ms. Cauveren,” he began with a tender kind of urgency, “I’ve read the reports. You suffered a great deal, and I want to tell you that I’m sorry.”

He admitted it was his first unsupervised call and that he was a General Practitioner in training, that he’d been afraid and uncertain. I listened quietly, and when he finished, I poured out my truth—not with anger, but with honesty.

My brother joined by phone, chimed in:

“Not every patient knows what’s wrong with them,” he said gently, “but my sister did. It’s better that you learn this lesson now, at the start of your career. She’s not here to ruin it—she wants you to learn from your mistake.”

His words steadied me. Every woman, I thought, needs a male protector who sees her pain and stands beside it.

I looked into Dr. de Bruin’s eyes and said, “I forgive you.”

He blinked and a look of stunned disbelief shot across his face. Then I told him about qadr, about how everything had unfolded exactly as Allah intended, and that gratitude—not bitterness—was what remained in me.

His supervisor exhaled audibly. “Your religion,” he said quietly, “has such a beautiful way of looking at it.”

When they left, I exhaled as if I had not done so in years. I felt the heaviness that had burdened my life for as long as memory stretched back, lift off of me.

A few days later, the female doctor came to see me, Dr. de Vries, accompanied by a representative from the complaint commission. She apologized, but her tone was stiff, her eyes guarded.

“Hmm,” I said softly, “your apology doesn’t feel genuine.”

She began to cry.

It was only then Dr. de Vries, let her guard down, and as we talked, I realized her arrogance had been a wall she, as a woman, had put up, trying to navigate a male-dominated profession.

This woman, who held such power over me that night, looked like a little girl.

I moved closer to her.

“Dr. de Vries… Sanna…I forgive you.”

She wept.

She wanted to know about my suffering. I told her that my suffering was a blessing and not a result of her mistake, but Allah’s mercy.

Both the doctor and the complaint commission representative started to cry again.

We talked a few more minutes, and the air was lighter when I escorted them to the door.

Before leaving, Sanna offered me her hand. And I offered mine back. She smiled, and I returned her smile.

Allah Subhanahu wa ta’ala says in the Qur’an:

وَلَمَن صَبَرَ وَغَفَرَ إِنَّ ذَٰلِكَ لَمِنْ عَزْمِ ٱلْأُمُورِ ٤٣

And whoever endures patiently and forgives—surely this is a resolve to aspire to.

Looking back across the tapestry of my life, I see now that Allah Subhanahu wa ta’ala had been teaching me forgiveness long before this day. My father’s murder had been the first great test—learning to forgive a killer, the hardest thing I’ve ever done. Every test from Allah has been a lesson in letting go.

“The power of forgiving is freedom, if you are able to firmly set in your heart that the greatest justice is on the Day of Judgment, and that Allah Subhanahu wa ta’ala is the One who can accept the repentance of others. Not because you forgive, does it mean you absolve them of the mistake. You can forgive, but ask Allah Subhanahu wa ta’ala to still give you the reward, and to give them what Allah knows they deserve.”

— Sheikh Yahya Ibrahim, London, 13 July 2019, Love Notes Seminar, the answer to my question of how I could forgive my father’s murderer.

I am free!

ٱلْحَمْدُ لِلَّهِ رَبِّ ٱلْعَـٰلَمِينَ ٢

All praise is for Allah—Lord of all worlds,

I hope we meet in Jannah, ameen.

Much love,

Nour Cauveren

P.S. Lighter, grateful, and full of joy. Alhamdulillah.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to all the sisters who showed me love—to those who came and recited Surah al-Baqarah for me. To my teachers Yafa (California), Maraheb (Cairo), Najla (Cairo), and Deena (UK): your patience, love, and support have been life-changing.

To my friends Aisha J. (London), Aishah J. (Bradford), Sarah M. (London), Fathima (Dammam), Rahma (Mombasa), Ghena (USA/UAE), Aisha M. (Singapore), Kulsum (Vancouver) my tahajjud buddy, Aminata (Paris), and my very special friend and former business partner Bunga (West Java) and her Ibu (West Java), and the countless sisters I cannot name—may Allah reward you all abundantly, ameen.

To my BFF

(USA) and Shanti (AMS by way of Roma), who washed my clothes and cut my hair with the love only a sister can give—thank you. And , you are loved, special, and cherished. May Allah grant you shifa and ‘afiyah ameen. And to my friend who likes to be known publicly as 🕊️(Doha)—see you soon in Doha, inshaaAllah.To my editors Nafisah and Medina

—thank you for supporting me.To my fellow substack writers

and thank you for reading, motivating and inspiring me.To Qasim, who asked me to test his app and let me be part of something bigger than myself—thank you. I am convinced you are going to revolutionize Arabic learning, InshaaAllah, and to be a part of it is a blessing. Thank you for your consistency and thoughtfulness. Watching your dedication and focus has inspired me to dream big and take small consistent action every day. I no longer hold myself back. Flow M. Vibes :)

And to Delo—I love you. Being your sister is an honor. Thank you for standing by me—for Sunday-morning coffee, for silent book clubs, and for that smile you think I don’t see.

Finally, to all my readers. Those who have written to me and those who read silently. I am grateful to you all. One such reader

has just launched her Substack. I am proud of you and thank you for inviting me to be a part of your journey. I look forward to seeing you shine! InshaaAllah.Alhamdulillahi rabbil alamin.

Nour, subhanallah, I only knew fragments of what you were going through and here you express it with such beauty and depth, it all becomes clear. May Allah reward you without measure for all you've been through. Thankyou for moving me so deeply today. Alhamdulillah for being able to accompany you in your writing journey. May you help and inspire millions of people with your story! Ameen!

Nour, I love you for the sake of Allah. You are a true blessing in my life. May Allah Subhanahu wa Ta’ala bless you, protect you, and fill your heart with peace and light.